Business

UK Court Rejects PwC Report, Deals Blow To dfcu In Crane Bank Case

By Gad Masereka

London, United Kingdom – In a ruling that has sent ripples through Uganda’s financial and legal communities, the High Court of Justice in London has dealt a significant blow to dfcu Bank, undermining the very foundation of its defence in the high-profile Crane Bank case. Delivered on July 24, 2025, by Justice Paul Stanley KC, the decision casts serious doubt on the credibility of the forensic audit that dfcu had relied upon, setting the stage for a contentious full trial in 2026.

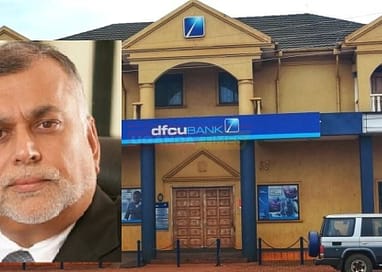

The judgment followed an application by Crane Bank Limited (CBL) and its shareholders, led by businessman Dr. Sudhir Ruparelia, to strike out parts of dfcu’s amended defence. At the centre of the dispute was the controversial PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) audit report, which dfcu sought to use as factual evidence to justify its acquisition of Crane Bank assets from the Bank of Uganda in 2017. The court, however, found that introducing the report in that manner would compromise the integrity of the trial.

“This is a heavy litigation,” Justice Stanley noted, referencing the more than 10,000 pages of pleadings already submitted in a case set to proceed to a 12-week trial in the Michaelmas term of 2026. He added that the way dfcu attempted to rely on PwC’s conclusions—without proper evidentiary support—posed “immediate questions” and risked obstructing fair preparation.

While the ruling does not prevent dfcu from referring to the existence of the PwC report, it explicitly bars the bank from using its conclusions as evidence of fact. “The PwC reports, whatever their merits, do not resemble a pleading,” the judge wrote. “They were introduced in a way that is inconsistent with effective preparation for a fair trial.”

The decision is widely seen as a sharp rebuke of dfcu’s legal strategy, which had leaned heavily on the PwC report to substantiate its position. That reliance is now significantly curtailed. Instead of bolstering dfcu’s defence, the report has been rendered legally inadmissible for its intended purpose—calling into question the basis on which the 2017 takeover of Crane Bank was executed.

Lawyers representing CBL challenged the authenticity, legality, and authorship of the PwC report, describing it as tainted and procedurally flawed. Among their objections was that the report was not prepared by PwC’s global office but by a local, unregulated entity falsely presenting itself as part of the PwC network. Multiple versions of the report existed, many of which lacked signatures, dates, or the necessary appendices that would support its conclusions.

Adding to the concern, the report was allegedly compiled without input from Crane Bank’s original shareholders, who claimed they were denied access to essential financial records then held by dfcu and the Bank of Uganda. This, the court heard, made it impossible to fairly assess or respond to the audit’s contents.

In striking down dfcu’s amended pleadings, the court awarded immediate legal costs of £90,000 to Crane Bank, with the final sum expected to exceed UGX 1.7 billion once fully assessed. This financial burden adds to the reputational strain on dfcu, which now faces mounting scrutiny both in the UK and back home in Uganda.

The broader implications of the ruling are considerable. It revisits the controversy surrounding the closure and sale of Crane Bank, a process that Uganda’s Parliament—through the COSASE committee—and the Auditor General have previously flagged for lacking transparency and procedural fairness. The court’s findings appear to support Crane Bank’s long-held claim that its closure was orchestrated under questionable circumstances, and that its assets were transferred in a manner inconsistent with due process.

Sudhir’s legal team has consistently maintained that the bank was neither insolvent nor mismanaged at the time of its takeover. On the contrary, they argue that Crane Bank was financially healthy, and its closure was the result of a deliberate scheme to facilitate a rushed, undervalued sale. The UK court’s rejection of the PwC report—the cornerstone of dfcu’s justification—bolsters that narrative and increases pressure on both dfcu and the Bank of Uganda to explain their actions.

As the case heads toward trial, all eyes will be on the evidence that emerges in court. The claimants will now proceed with arguments that Bank of Uganda manufactured instability to justify a politically and commercially motivated handover, and that dfcu knowingly participated in that plan. The trial promises to be a test not only of the parties involved but of Uganda’s financial governance and regulatory accountability.

The outcome will likely shape legal precedent for how foreign courts treat cross-border regulatory actions involving African financial institutions. In the meantime, the London ruling stands as a stark reminder that justice, though sometimes delayed, can deliver sharp clarity when it finally arrives.